Colonial binary understandings of gender, race, and sexuality have deemed queer and POC’s bodies as unnatural. We do not live in a world of black and white; science has trouble categorizing species, species defy colonial gender and sexuality expectations, and humans have layers of complexities. The existence of POC, queer people, and queer ecologies defies heteronormative, colonial, and capitalist systems because we do not fit in a box, we do not fit into heteronormative society and therefore, in the eyes of this society, have little value. In a western society, everything must have use or capital: the people, the objects, the land. If the people do not fit into their prescribed roles, if the land is depleted of “resources”, if the object does not serve a purpose in this society’s eyes, this system begins to break down, cracks begin to form.

And to the earth they shall return

Reciprocal care for survival in a precarious world

But what if we can shatter these cracks through radical care? We must take care of ourselves and each other, reconnect and ground ourselves, and allow ourselves and the Earth to heal in order to carry on. This collective action of care has begun to break global capitalism down around the world. Care is fundamental to social movements. In the face of state-sanctioned violence, economic crisis, and impending ecological collapse, collective care offers a way forward. By centering care, we can re-imagine our world and the inequitable dynamics that currently shape our social landscape. And by creating communities and connections with each other and the Earth, we are resisting colonial systems so insistent on keeping us apart, on keeping us from caring for one another, healing, and having space to breathe and imagine. We need to use imagination to break down barriers of our past, to open up new futures. What does this radical and reciprocal care look like?

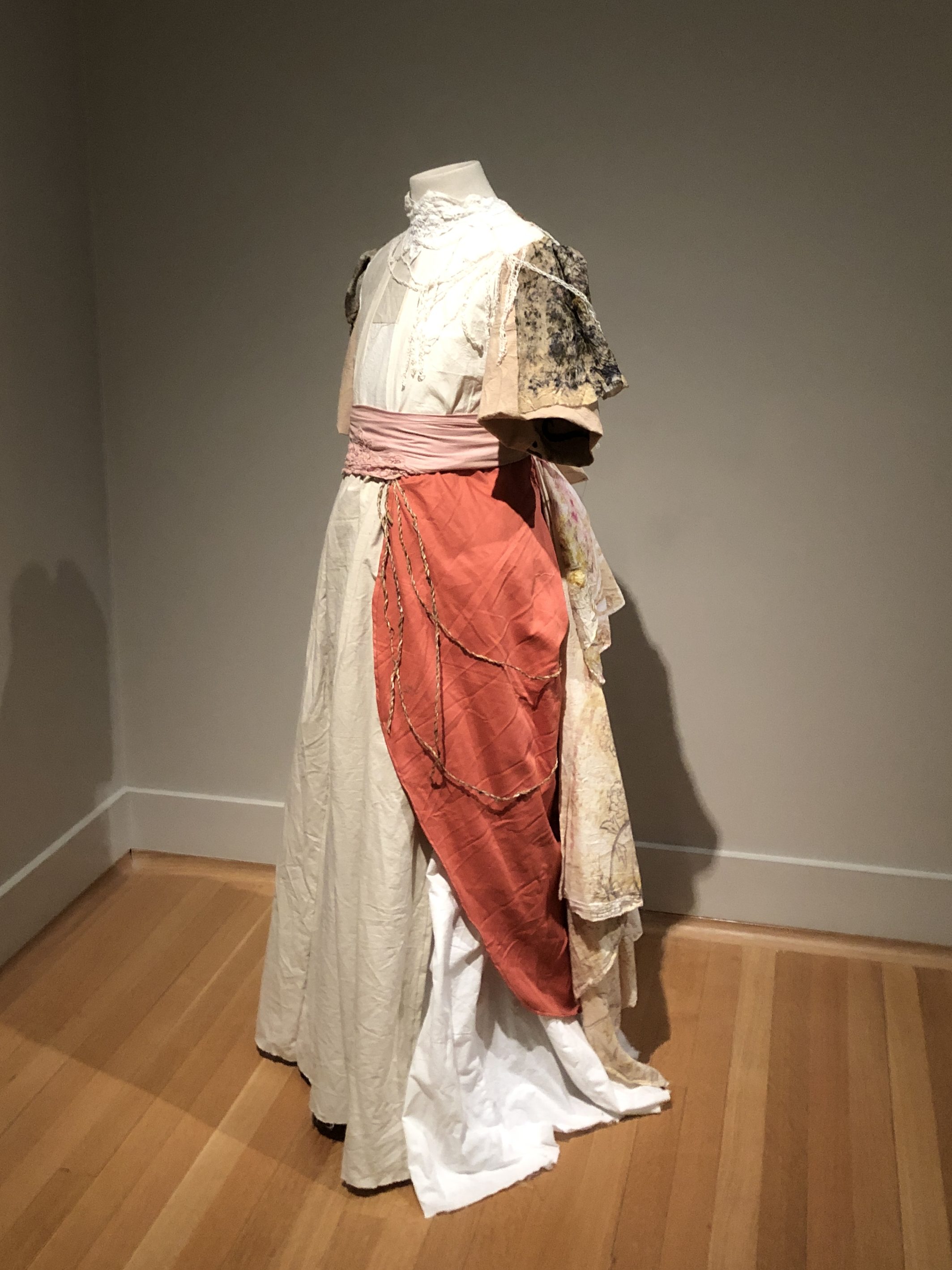

Garment modeled by the lovely Livia Miller

Scrap cotton, silk and linen, daylily cordage, natural dyes.

Textiles and garments offer a vessel for this care. Textiles hold a gendered and racialized past, they have been intertwined with global capitalism for so long, and yet textiles is also a tactile source for care. Blankets, clothing, furniture and more; all these textiles hold meaning for us. Our orientations towards our textiles affects our perceptions of them and of ourselves. Classically, a dress would be worn by a woman in western society’s eyes. But why? Why can’t we imagine, and shift our orientation towards a dress as a gendered object to a queer object? Acceptance and care towards QTBIPOC bodies and the Earth can allow for a vibrant future, and garments and textiles can be instrumental in this. Clothing has been harmful to the Earth and to the people wearing them. And yet, textiles can be so healing, so full of care and memory. This garment aims to shift our orientations towards a decolonial future of care and reciprocal relationships.

This garment focuses on cycles of life and decay, on our orientations towards objects as gendered, racial, and capitalistic objects, and foremost it focuses on the importance of care. It is meant to challenge the past of the inherent vice garments, why they have been conserved, why we hold on to textiles and objects so tightly, what the future of these garments are, and questions if there is a death for our belongings. Does the use of the queer garment disappear after it’s unwearable? Or does it re-orient itself to a new life, making connections with the soil, the fungi, the bacteria that it feeds? This garment lives a decadent and nourishing existence, in relation to queer bodies and to the Earth.